Andrew: Three messages before we get started. First, do you need a single phone number that comes with multiple extensions so anyone who works at your company can be reached no matter where they are? Go to Grasshopper.com. It’s the virtual phone system that entrepreneurs love.

Next, does anyone you know need a beautiful online store that actually increases sales but is easy to set up and manage? Send them to Shopify.com, the platform that top online stores are running on right now.

Finally, do you need a lawyer who actually understands the startup world that you and I live in? Go to WalkerCorporateLaw.com. I’ve known Scott Edward Walker for years, so tell him you’re a friend of mine, and he’ll take good care of you. Here’s your program.]

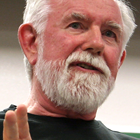

Hey everyone. My name is Andrew Warner. I’m the founder of Mixergy.com, home of the ambitious upstart, and the place where founders come to tell the stories of how they built their businesses. In this interview I want to find out how an engineer and painter launched the pioneering animation studio Pixar. Alvy Ray Smith co-founded Pixar, the dominant animation studio whose beloved and profitable movies include “Toy Story,” “Finding Nemo,” and “The Incredibles.” In 2006, it was acquired for $7.4 billion by Disney, a company that its founders admired for years, but it all started in 1974 in a New York garage, as you’ll hear in this interview. Alvy, welcome. Thanks for sharing the story.

Alvy: Hi. Happy to.

Andrew: Where were you when you saw “Toy Story,” the first feature film that Pixar put out?

Alvy: I was in the audience of the premiere, the special showing for Pixar, of course.

Andrew: Do you remember how you felt when you saw this dream that you worked so hard for up on the screen?

Alvy: Total elation. Took us 20 years. For the first idea on Long Island in the mid ’70s, took 20 years. It took Morris Law to increase by a factor of 10,000, is another way to put it.

Andrew: You were waiting it out. Waiting for the hardware to be capable. The software to develop to the point where you needed to.

Alvy: And to crack a few of the crucial algorithms, like motion blur, which were fundamentally important.

Andrew: There’s a great piece in David Price’s book, “Pixar Touch,” which I use a lot to research you, where he talks about that and the significance of it. I’ll come back to it later on in this story, but before we started, you said, ‘Andrew, the story of Pixar hasn’t been told well.’ I’m wondering what have other people gotten wrong about it?

Alvy: First of all, David Price’s version is accurate, but I’m not sure how many people have read it. Also, Michael Rubin wrote a book called “Droidmaker,” that has this story well told up to the spinout of Pixar from Lucas Film. You introduced it right. I like your style.

Andrew: What do most people get wrong? The idea that Steve Jobs launched it and believed in it throughout, and that it got formed at that point?

Alvy: Let’s start right there. Steve Jobs wasn’t part of the story for the first decade. The group now known as Pixar began on Long Island working for our first patron, who was this amazingly interesting, shall I say, man, Alexander Schure. Uncle Alex, we called him. Uncle Alex was the first patron of three to jump over the cliff for us, and he was the only one of the three who lost everything. The other two became billionaires, [??] and George Lucas and Steve Jobs, of course. Uncle Alex was the first one to say, ‘We can use computers to make animated movies.’ He put together a complete old fashioned cel animation studio on Long Island, on the fabulous north shore of Long Island, I should say, Great Gatsby land, at his school, the New York Institute of Technology, which was really four estates from the north shore all coddled together. The mansions on this estate were the buildings of the campus. We were in one of those. Not part of the school itself, academically, but there to, as he put it, ‘Speed up time, eventually deleting it.’ That’s the way he spoke, by the way. No idea what it meant.

Andrew: I still don’t.

Alvy: I don’t either.

Andrew: But he was a visionary who wanted to see computers create feature films, see computers create what we saw on the screen when we saw Toy Story.

But I’m wondering why as the founder of the New York Institute of Technology he would want to be the next Disney.

Alvy: You said it right. He did see himself as the next Disney. There was a strange association between New York Tech and Disney. There’s a building on the campus, a mansion, [??] all mansions. One of the mansions is called the De Seversky House. De Seversky wrote, he was a General, he wrote ‘Victory through Air Power’, it was an early book praising the idea of an Air Force instead of an Army.

The Disney Corporation made one propaganda movie. A lot of people don’t know about this. It’s called ‘Victory through Air Power’, it’s based on De Seversky’s book. I think that might have been the associate and since De Seversky was a close personal friend of Uncle Alex, I think that might have been where he got the idea that he could be a Disney act.

Again, his mind was impossible to fathom.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: But he, whatever the reason, he put us, he build for us, he paid for us, we had the best of [??] world, the best computer graphics in the world. It was a mecca, everybody came from all over the world to see this place. It felt like we had a dream, we were on estates, we worked in mansions, we never had to know where the money came from, we never knew where the money came from because he didn’t let us know .

But we got what we asked for. So, for example, we got the first 24 bit-frame [??], the first fullpower frame [??], you know, what’s commonplace now on phones, 24-bit memory. Then it was called frame-by-frame, it was the size of a refrigerator, it cost $1 million so he bought us two because I just said it would be a good idea. That’s the way he worked.

Andre: How fortunate to have that . But you know what, fortunate is great but how you ended up there is not just luck. I’m wondering how you, a guy who I think you were on the west coast at the time, how do you end up going to New York and being a part of something like this instead of reading about it the way most people would and saying ‘Boy, this is fantastic. One day this will happen.’

How do you become the guy who makes it happen?

Alvy: Oh, that’s a good question. Because the people who found their way to New York Tech just found their way. It’s like, started looking for where is this happening in the world and we [??]. I was at Xerox Park, the famous [??] research center when the personal computers as we now know it, except they didn’t have Skype yet was being invented. You know, Xerox Park had the first personal computer, the first ethernet, the first mouse, the first Windows based operating system, the laser printer and colored graphics [??] my buddy Dick Shoup.

Dick Shoup had built the first paint program, a machine hardware and a software [??] nothing to be purchased in those days where an artist could paint on a computer and that was what I was looking for, a way to combine my artistic skills with my programming skills. Soon as I saw it, I knew that was the future and I never looked back.

Andrew: And then you were just hunting for a place to help make this happen and you didn’t wait for an invitation, you didn’t wait for a job opportunity.

Alvy: Well, it was a little bit encouraging. Xerox Park fired me.

Andrew: Because?

Alvy: They called me up one day and said ‘You’re fired’. I said ‘Why?’. They said ‘Well, we’ve decided not to do [??]’.

But the future is colored. You own it completely, they said, my boss said. That maybe true but the corporate decision is to go [??]. So I moved back with my buddy David D’Francisco, an artist I had paled up with for a National Endowment for the Arts grant to find the next [??]. First, we went out to Salt Lake where the University of Utah famously had some great computer graphics people. One of my future partners at [??] came from, and they said, they looked at us, freaky looking artist guys. I had my hair done to the small of my back and they got hair up to there and they looked at us and said ‘You know, we’re department of defense funded. There’s no way we can deal with you guys here. But there’s this crazy man from Long Island who just came through. He has an animation studio and he wants to make movies. If I were you, somebody in Utah said, [??], I would get on the next plane.’ That’s pretty much what we did.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: When we got there, it was everything a guy, everything that they promised, including the next frame buffer, the next color graphics.

Andrew: And Ed [??] was there. He was already leading the operation.

Alvy: Ed would have been there a couple of months. I don’t know. Three, four months. Something like that. He had been at University of Utah and he wanted to be in animation, too. He was an aficionado like I was. But he had given up hope. His PhD adviser, Ivan Sullivan, had started a company that was going to go to Hollywood and use computers to help make movies. Ed was waiting around for a job with Ivan in Hollywood. Never happened. Recession got him. But Ed had a family, a wife and kid. So he had to take a job. He took it in Boston at a CAD company, a computer aided design company called (?).

About a month later, Alex, Uncle Alex, our famous Uncle Alex at New York Tech was looking for somebody to run this set of equipment he’d just bought on an eChat in Salt Lake. I told him, “Well, you should look up this guy, Ed. You probably can’t get him because he had to take another job”. But Ed left, of course, when he heard about this and came to the fabulous North Shore this his office mate, Malcolm Blanchard. When David D. and I showed up from Xerox Park we met Ed and Malcolm, who had just arrived from, basically, Utah via Boston. We were the original four for the next 20 years.

Andrew: Why didn’t you stay there? Alexander Shore had the vision like you did to create an animation studio. In fact, he was already animating, I think, using cel technology. Right?

Alvy: Oh, yeah. He had the old fashioned cel technology, cel animation technology, where they actually draw the original paper and pencil images and then outline them in ink and fill in the colors torturously with opaque paint. It’s the old fashioned way. It’s the way Disney did it, until we came along.

Andrew: Until Pixar digitized it for them.

Alvy: Actually, did it at Lucas Film but Pixar finished the job.

Andrew: He had the same vision you did, to computerize this. And he had the money to do it but it wasn’t a good fit because…

Alvy: He didn’t have the skill. Now, he wanted to be the next Disney and he had the 100-plus man team of animation people to make the movie. And they did. They made Tubby the Tuba, which, I’m sure you’ve never seen because it was pretty bad. In fact, we all went to sleep in the front row at the premiere in Manhattan because it was bad. You just couldn’t stand looking at it. It was a bad story. The animation was good. The old-timers were really good animators but the story was bad, the music was bad, the dialogue was bad.

Andrew: You couldn’t hire somebody to fix that?

Alvy: There was lint on the frames. Without anybody saying anything, we knew we had hitched our wagons to the wrong star.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: For example, one of the young animators, one of the few animators then who would talk to us and wasn’t frightened of us, came up afterward to me and said, “You know, I’ve just wasted two years of my life”. He left immediately to work for Ralph Bakshi. We realized this guy was not going to take us into the future. We had already had the vision by then that we were going to be the first people to make a digital movie. It happened on Long Island. This clearly wasn’t the guy.

Andrew: Before we talk about where you went next, at the next of the three patrons, what did happen to Alexander Shore?

Alvy: Well, he continued to run his school, New York Tech. He continued to have a computer graphics lab there. But, essentially, nothing serious ever came out of it.

Andrew: You say he went bankrupt. Was that from buying all that hardware?

Alvy: He spent, oh, $15 million, which is $50 million now, on us and drove the school into serious financial troubles, so far into trouble that his sons took it away from him.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: The school, by the way, is now a good, functioning, worldwide institution. But I met the President, Ed Guiliano. He explained to me how close to the edge we, the computer graphics lab, had driven the school. I said, “I’m sorry. We didn’t know. We had no control of the money whatsoever”.

Andrew: No control, apparently, even your own money. There’s a piece in David Price’s book where he says you engineers wouldn’t even cash your checks. You’d forget to cash the paychecks.

Alvy: Oh, we never did anything but work. We didn’t even want to go to sleep. We were having so much fun. It was partying.

Andrew: Because you were obsessed with this vision?

Alvy: No, that sounds too fancy. We were the first people to have full colored graphics. It is hard to look back when it did not exist, but we were the first there. We were on the land on a new continent for the first time. We got to pluck all of the low hanging fruit. We got to name everything and everything we say every moment of the day was new and exciting, thrilling, and beautiful.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: It is hard to get across how [??] amazing this time was. We were all living on an estate, working on an estate. I lived on David Rockefeller’s wife’s estate a couple of miles away. There were mansions there. For a kid from New Mexico, this was quite a fantasy, but it was real.

Andrew: All right, I can understand that. Now that you put it that way, absolutely I could understand it. All right, and now there is an opportunity for you to go to the west coast, and that comes up how?

Alvy: We always thought it would be Disney that would come rescue us. Every year, Ed and I would usually make a secret trip of pilgrimage to Disney in Burbank. Assuming that one of these days they would take us, they were the great center of the great animation that we had grown-up with and loved. They were wealthy. It was well known that Disney had the money and we were going admit an expensive proposition. We were a very expensive proposition and he could set somebody hundreds of millions across our various [??] before we finally made it. However, every year Disney would say no. I remember one of the first trips we went on out there and he said, ‘Do you boys do bubbles?’ Well, we could not do bubbles.

Andrew: Why bubbles?

Alvy: Well, it did not matter. The next year it was smoke. It was as if they did not get it, that computers can do anything eventually, but it is one of those things you just have to know. We knew it but they did not. Their technical people knew exactly who we were and over the years, we made fast friends with the complete technical level of people at Disney and it paid-off handsomely later. However, the management, you know, one of the managers was a professional football player. He did not have a clue what was going on. He had married Disney’s daughter and that was his qualification.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: They were driving the place into the ground. The technical people knew that this was happening and they knew we had a solution, but they could not convince them for many years, that this was the right thing to do was to go with us. Therefore, he came along, this person George Lucas and we were not expecting him at all. His first movie, Star Wars, had just come out and it flipped us all out. When he did call, I should say that Francis Coppola called the day before George Lucas did, their people did, not themselves of course. I did not trust the team that called from Coppola’s, in fact they coked-out a few years later, so it was a good call. However, the next day we got the call from Lucas’s people. In my opinion, Coppola is the greater director, but he is also flaky as far as [??] angel things. Up and down, and up and down, make a fortune and lose a fortune. George Lucas is slow, steady, and competent. It was a good bet to go with him and that is what we did.

Andrew: He also seemed to understand technology, though not as much as we thought he did.

Alvy: He had used computers. It was part of their marketing in Star Wars, that computers were involved.

Andrew: Oh, OK.

Alvy: In fact, there was a computer graphic sequence in the first Star Wars and it was black and white. I do not if you recall that or not. Our friend Larry Cuba did it. Therefore, to us this meant this was a great director, he is successful, he knows how to make a real motion picture as opposed to Uncle Alex, and he already knows about computer graphics and that is way he wanted us to come. Now the wording was slightly different. The wording was, ‘Will you guys join us and digitize to bring the technology of Hollywood film making into the future.’ He was stuck in the 40s level of technology. We said we could do that, but we also make content. I was already in the Museum of Modern Art and we had already done commercials on television. We liked to make things. David and I were there so we could satisfy our NEA grant to make art on this thing. We wanted to make content. George apparently did not get that, but we did not know that at the time.

Andrew: He did not want you making content. I know one of the things he wanted you to do was to help him digitize his bookkeeping, like bring him into QuickBooks, which did not exist at the time, but for filmmaking, what was it that he was looking for?

Alvy: Well, he had a great vision there actually. It was not exactly ours but it was part of it. For example, he wanted to make audio all digital and audio editing digital. [??] audio digital, which all makes sense and we did it for [??]. Same thing with video. Film would be the output, you’d get all your dailies and your editing with video under computer control. Makes perfect sense, and that’s how it’s done now.

Andrew: Essentially at the end of this interview what someone will do here is digitally edit this, cut up the part of the conversation that we had before we start . . .

Alvy: [??] idea, right? It’s a perfectly reasonable thing to do, and he had the money to pay for it before it became common place. That was good. The third thing he wanted to do, and this is where I come in and the group now known as Pixar, he wanted to digitize the optical printer, which is the unsung hero of Hollywood. It’s the machine that would composite one film strip over another, rocket ship over a star field, for example. That machine was under computer control in the first movie. Not the same thing as computer generated content. It was computer controlled camera. Not the same thing, but that’s what my group, the computer graphics group that wrote this film, built for him. We called it the Pixar Image Computer.

Andrew: Is that right?

Alvy: Yes. That’s where [??] came from.

Andrew: Even back then it was called the Pixar Image Computer, under Lucas?

Alvy: Yes. By the way, Steve Jobs hadn’t shown up anywhere yet. That’s part of the story.

Andrew: This is what some people think is the back story, but this is the middle of the story.

Alvy: For the first film, like I said, by the time we finished Lucas film, we’d already been on the big screen, we’d already hired John Lassiter [SP], we already had named the company.

Andrew: The name came from where? From you?

Alvy: The name came from my background in New Mexico. I grew up in New Mexico where Spanish is rampant, as everybody knows. Election time, especially we’re aware of this. I was enamored of this word ‘laser’ because it’s a noun that looks like a Spanish verb. Spanish verbs all end in ‘ir,’ ‘er,’ or ‘ar.’ I got my team together to name [??] before it’s all together, in a burger joint to name the machine, not the company. I said, ‘I want a name that’s like laser. It’s a noun, but it looks like a Spanish verb.’ I proposed Pixer and my colleague Loren Carpenter said, ‘You know, Alvy? Radar is this really tech sounding word and it’s got the ‘ar’ on it.’ I said, ‘That works too. That’s one of the endings.’ Pixar.

Andrew: That’s how it became Pixar?

Alvy: Yes.

Andrew: Under Lucas, the computer was named Pixar?

Alvy: It was named Pixar. We had a terrible reputation for not being able to name things, our group had that terrible reputation. For example, we were called a place holder name at Lucas Film, the computer [??]. We all hated it. We wanted a sexy name like Industrial Light and Magic [SP]. We, being a very collegiate group, set up a contest. If two people had agreed on a name, we would have gone for it. No two people, and we generated thousands of names. No two people could ever agree and we got stuck with Computer Division.

Andrew: That was the official name? I actually didn’t realize it was the official name until I saw it on Wikipedia.

Alvy: That’s it. Eventually when Ed and I got around to spinning out the company and I needed to send a document to the California Secretary of State to incorporate it, it needed a name. We’d have been using place holder like [??]. It was DIFIP, almost an acronym for Digital Film Printer, which was [??]. G-effects was another name we used to [??]. Finally, [??] same group was trying to name the company. Same failure. What two people would agree? Finally, in desperation I said, ‘There’s this word that people are already associating with our group, Pixar, that we could use.’ The response was, ‘OK.’

Andrew: What I’m wondering is, under Lucas you were trying to become the next Disney. Not any individual person, necessarily, but as a company and again, under Lucas, you can’t do it. Why don’t you just say that’s it?

Alvy: Let me change your wording a little bit. We did see ourselves as the next Disney. We saw ourselves as the next Disney. We saw ourselves as the creators of the first digital movie. It turns out that the animation was the natural way to go to do that, but if there had been some other pathway to the first digital movie, we might have taken that instead. In fact it can be argued that Rescuers Down Under which was the first movie built on our system, the CAPS system that this indeed was the first digital movie. but I don’t call it that because the art was still created pencil on paper. Whereas Toy Story had all of the art created in the computer as well as the movie in itself.

Andrew: With The Rescuers Down Under it was basically adding color, filling in, drawing within the lines.

Alvy: [??] sell animation technique two dimensional could have done all of it done digitally except for the original drawings. Of course the exception there is the key you know. Everything, the art.

Andrew: You know I want to continue with the narrative, but first I’ve got to ask this that I know that there are people who are listening to us who are struggling right now who are saying to themselves you know what I have been working at this for a whole year and got no results. I’m going to keep at it or I’ve been working at this for 7 years not seeing real results, I’m going to keep at it and they’re going to say because Alvy Ray Smith kept at it for 20 years until he got to see Toy Story on the big screen I am justified to stick with this even if I am not seeing my big result yet. What do you say to them?

Alvy: The way you word it, it’s a good way to word it and I had not really focused in on what… If there had been no rewards between where we started and the movie 20 years later I don’t’ think I could have stuck to it, any of us, but I tried to express earlier how the world we were in was so exciting we couldn’t go to sleep and it remained that way for decades because everything we touched continued to be the first. It was so much fun. That’s my largest message to them. We had a ball.

Andrew: It was the fun of the process and also it was milestones along the way that felt rewarding?

Alvy: You know we were putting together this team of first class scientists finding their way to our group. I mean a lot of people wanted to make movies it turns out and they would just find their way. So we had a world class group of people who were solving the technical problems that were required to solve for the future of movies like [??] I mentioned earlier.

Andrew: Because you were working on such a big mission and with a big brand name in this case, other people gravitated towards you and wanted to be a part of it.

Alvy: Yes. So I guess another way to say this is we were all really academics at heart. Our reward wasn’t money. It was the fame you get from your colleagues. That’s the pay in academia.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: And we had immense fame. Every year there is a big conference called SIGGRAPH. That’s the large . . . you know it’s up to like 30,000 to 40,000 people a year now. It’s where you go once a year to show off what you have accomplished to your colleagues during the preceding year. The film night there could be the highest moment of your life. There would be 5000 of your colleagues all talking the talk, you know if you could do the technical stuff right down to the floor. They didn’t’ have to be told. If you showed something new to them that had never been done before, they would be on their feet screaming. An audience of 5000 people screaming is quite a reward. So we would go for that.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: And we would frequently get it because we had such a high powered group. Every year we would you know starting from 1989 Lucasfilm on we would dominate the place. Again like you said the magic of Lucasfilm made it easy for me to acquire first rate program.

Andrew: You mentioned one of the challenges of motion blur.

Alvy: Yes.

Andrew: How do we explain that in this interview? What’s an easy way to show people what that challenge was and how you guys overcame it?

Alvy: If you don’t have motion blur the result is ugly. Ray Harryhausen was a famous film maker who in the early days made movies like Jason and the Argonauts where we had skeletons, but they were done with stop motion and they would jutter across the screen. It hurt to watch them move across the screen because they didn’t do what a real camera sees. If you think about a real camera it shutters open for a finite amount of time so if anything is moving during that finite amount of time, something in motion blurs across the frame in the direction of the motion. So what we had to do was simulate that effect. That’s why we call it motion blur, but in a very efficient way. It took a lot of computer horse power, which we just simply didn’t have in the early days. I emphasize the computer type of speed factor of 10,000 during my 20 years to get from the idea to the execution of the idea.

Andrew: John Lassiter. You mentioned him. He came into the picture how?

Alvy: One of our many secret trips to Disney. We continued those trips even during our years at Lucas Film. One day, we met a young animator there, John Lassiter. When he was young, he wasn’t frightened of us. Like I mentioned earlier, these old animators on Long Island were scared to death of us. They though sure we were going to take their job away no matter how we. Not only do we not do. Computers can’t do the art. We can take away the grunt work but not the art. That’s. It just doesn’t work that way.

John didn’t have to be told that. He knew. He’d already worked with a group and knew computers weren’t scary. In fact, he saw the future, I think. Hitched his wagon to our star. But he was working at Disney. We couldn’t touch him. I should. I like to tell my story about how we bonded.

He took Ed and me down into the archives of Disney and said, “Well what do you want to see? You want to see?” “Anything?” “Yeah anything.” Well, I was an old [??]. I told myself how to animate out of Preston Blair famous $1.50 how-to book. I said, “I want to see Preston Blair’s dancing hippos from Fantasia.” John says, “OK.” And he walks over and looked up on chart. [??] has the manila envelope with a manila folder and he flips the through the drawings like animators do.

Andrew: Wow.

Alvy: Old Preston Blair drawings. And there they were. The dancing hippo. And, then he said, “Now what?” Elephant scene from Dumbo. He went on. Instant bonding. It was great but we couldn’t touch him.

Andrew: How did you know how talented he was?

Alvy: Well, somebody told us. Somebody, probably at Disney, told us that he had been the student academy award winner at Cal Arts. Cal Arts was the art school in southern California, built by Walt Disney to train animators for his own company. And John had gone through the class of training and had been the best student. And I think we saw. Frankly, I’m a little fuzzy on that, but we knew he was a first rate animator.

Then, I’m sure he must have shared his magi test that was really [??] he was going to be working at. Then a few months later, Ed’s on the Queen Mary. The old Queen Mary’s a conviction center in Long Beach California. Ed was there and we were having our daily business call. I saw so and so. And oh, by the way, John Lassiter came by and he’s not working at Disney any more. Ed, get off the phone right now and go hire him! Yeah that’s a good idea. And he did and John came. What we didn’t know was John had been fired. He was too embarrassed to tell us and frankly, it wouldn’t have mattered a bit but he thought it would. So, he didn’t tell us for years and years that he had been fired. Probably because I think it was because he wanted to use computers.

Andrew: And he was the story teller who kept Pixar from being like the New York Institute of Technology.

Alvy: He was the guy. He was the talent. He was the missing ingredient. Raw, reaching talent of a kind that he can’t explain and I can’t explain. I think it’s the same kind of talent that great actors have. That great animators and great actors have exactly the same skills. Great actor convinces you that he or she, his or her body is someone else’s. Snip it you buy it. An animator convinces you that a stack of [inaudible] is somebody completely different than he’s thinking and moding and emotional. It’s amazing. I thought I could do that and it turned out all I could do. I mean I trained myself from Preston Blair’s book. I could make things move great. Convincingly. But the extra thing about putting a consciousness into the animation and the motion. Haven’t a clue. John can do that. That’s why he gets the big movie star bucks. And he does. And by the way, Pixar does hire animators by how well they act.

Andrew: Really?

Alvy: I talked to actors about this. Like Brian Cox. He’s a great Shakespearean and stage actor in New York. And I talked to him and he said, “Oh yeah. That’s exactly the same thing.”

Andrew: So, then, what am I thinking of? The next big step is that you need to leave Lucas Film because of…

Alvy: Well, before it gets there, I’d like there’s one really important thing, development and I mentioned that a couple of times. It’s the [??] project at Disney came along.

One month after Eisner and Wells finally took over the company, it was failing under this bad management that we first encountered there. Roy Disney engineered the takeover of the company by Michael Eisner and Frank Wells. One month later they knock on our door and said ‘You know that thing you always wanted to do with us? [??] cel animation. Let’s do it.’

It took me 18 months to negotiate it, or 16 months, excuse me, 16 months to negotiate. But we negotiated this computer animation production system with Disney which completely replaced their traditional system with a digital using Pixar image computer by the way of [??].

And why that’s important is that was the bonding of the two companies. It was an incredibly successful project. It was one of those deals made in heaven where we outperformed what we contracted to do and they did too. They had part of the contract was they supply the logistic software, [??] better than we did, of course. They overperformed on their end,, we overperformed on ours, came in center cheaper, larger set of features. It was a mutual admiration setup and right then and there which eventually resulted in the purchase of [??].

Waited so long is the question to me. Because if we think about it, they could have had us for free in the early days. We were on our hands and knees [??] . Then we came to the part soon where Steve Jobs steps in and do the financing of Pixar. Could have been Disney.

Andrew: It was $5 million.

Alvy: $5 to $10 million they could have had us and then all those years when Steve tried to sell us for $50 million they could have stepped in. Eventually [??] $7.4 billion doesn’t really make much sense but that’s the corporate world I guess.

Andrew: Do you feel that maybe if you were a negotiator the way that other corporate tycoons are, that you could have made Disney want it but you were more of an artist and engineer and that’s why you didn’t have the ability to make them buy it?

Alvy: You’re probably right. [?] and I were not businessmen. None of this group were businessmen. We were all academics [??].

What finally made me start thinking about it was our college Jim Clark. You may know Jim Clark, he started Silicon Graphics and then he started NetScape. He’s one of my billionaire friends. And he was at New York Tech with us. And got fired, by the way. We saw how litigious [??] Alex could be. But more importantly, oh, by the way, Jim and I grew up 60 miles apart. I was in New Mexico and he was 60 miles away in [??],Texas so we were homeboys, which is [??]. we’ve been friends because of that.

When Ed and I finally did get around [??] to starting a company, I called my buddy Jim and said How do you do it? He says, Oh there’s nothing to it. Take about a year and you’ll learn all [??] on how to do it and I think he had a higher opinion of our intelligence that we actually showed.

Andrew: At least when it came to business.

Alvy: Yes, right.

No, what happened. One other thing before we left LucasFilm that’s important. [??] first movie then.

Andrew: I’m sorry. That didn’t come through.

Alvy: The first movie at Lucas Film.

Andrew: What was that?

Alvy: It was going to be called ‘Monkey’, ‘Bad Monkey’. It was a famous set of tales in Asia, the journey to the West. Tales of travel that built up around the journey of a Buddhist Monk from China back to India to get the Holy text of Buddhism to bring back to make Buddhism a fully fledged religion in China. And these tales are strange ones. There are hundreds or maybe thousands of them. I have several sets of this Journey to the West. It reached four volumes thick. The mock head companions on this trick. A monkey with superhero powers. Pig and a couple of others. And the monkey. So, kids in Asia are brought up with monkey stores. Monkey, a young person really with too much power. Because of his youth, he’s always screwing up. He’s just. Everything gets out of control. That’s the general basis of all the stories. The character.

So a Japanese company came to us and said, “Well, let’s make the first movie about monkey.” Well, I already knew about monkey. I’d been to China in 1978 and I was in love with monkey and the idea of that being the first animated movie was rather attractive to me. And we got a long ways on the negotiations to making that movie. John Lester was already doing the story boards. When I started running the numbers, immediately start to happen. So, well it’s about time to run the numbers and just find out what. We’re going to have to make a deal here one of these days. What’s the number? What’s the magic number? And, it had to come out about $20 million or it wouldn’t have made financial sense in those days. It came out at $50 million. I mean this was just me adding. The first pass was $50 million which mean the real number was probably larger.

Andrew: To make the film?

Alvy: To make the film. And nobody ever made a film like this before and suddenly it occurred to me, “You know, this one is blindly. It’s too soon. We’ve got to wait for 5 more years. It’s too soon.”

And I had to pull the plug on that project. Again, Steve hadn’t shown up in the picture at all yet. All right? Here’s this. All right? He does show up here. Why? Because George Lucas got a divorce. George and Marsha Lucas. Divorced and in California. Fourteen [??] to each spouse. So, I went into bed. Since we talked about everything and said, “You know, George just lost half his fortune. He can’t afford us anymore. He never really got us anyhow. Let’s start a company. We’re going to lose this world class team. It would be a sin.” Is the word I used because I’d grown up Southern Baptist and he’d grown up Mormon so I knew he knew this word. So, Ed says, “OK.” And literally, we went across the street to a bookstore and we were in Marin County, California and bought four, two each, books on how to start companies. That’s when I called Jim [??]. That’s when we started to make the transition to businessmen. The weird thing is that it worked. It almost didn’t but it did. And frankly if we hadn’t had such a weird money man as Steve Jobs it wouldn’t have worked, I don’t think. He was, as far as money goes, he was great.

Andrew: He just kept funding the business.

Alvy: Be before Steve shows up, Ed and I went through every venture capitalist on Sand Hill Road, that fabled venture capital street in Palo Alto. We could get in their doors which most entrepreneurs can’t because we were sexy. We were Lucas Film. We were talking about movies and things. So, all the venture capitalist firms would listen to us and Ed and I got great exercise. We were learning fast. [??] from zero from those books we bought. We learned how to present a company and talked financials and PNLs and [??] and all that stuff. And negotiation. We started to learn negotiation. But we didn’t fit any of the ABC formula.

Andrew: Because?

Alvy: We were forty new people. We already had our prototype, Pixar industry computer. By the way, we knew we couldn’t make a movie yet, right? I’d just figured that out. So, what we’re going to have to do. I remember Ed and I saying, “What are we going to do?” You know, we started a company but what are we doing to do? OK. Well, software can’t pay for forty people which was the size my computer graphics people at Lucas. Only hardware would pay for it. But we had a prototype piece of hardware. Let’s call it Pixar Industries computer. Why don’t we go into production with the prototype? That’s just standard hardware business in Silicone Valley. And we’ll just wait. We’ll make money that way and maintain the animation team and wait for [??] bring us the horsepower we need.

Andrew: Throughout you were making commercials. Why not become a commercial production company and wait for [??] to allow you to move on to half hour shows and then from there progress?

Alvy: We didn’t do commercials until we were Pixar.

Andrew: I thought you did at NYIT. No?

Alvy: The non-for-profit. That’s a non-for-profit institution supposedly. So we just made. It was just the fun of making it. We didn’t make them for money. But, I don’t think so. It was just [??] what you could do. Nobody’s seen computers make anything in those days.

Andrew: Because when it came to hardware, you guys were even talking to Siemens about acquiring the business to use the Pixar imagine computer for cat scans so doctors can look at scans in high quality 3D views. It’s just amazing to go.

Alvy: [inaudible]. We decided to go strategic partnership with some large corporation. These are all the standard business techniques. Right? And Lucas Film is going to get a piece of this. So, they’re very interested in what happens and they’re helping. They thought they were. So, we went through twelve, fifteen corporations. We named some of them. Scanner print company. Scanning companies. Phillips in the medical business. General Motors in the car design business and that got very close. General Motors had a division called EDS which was electronic data systems founded by Ross Perot.

Andrew: The millionaire.

Alvy: So, this is [??] of General Motors. And Phillips medical division decided to team up and fund this start up company that Ed and I were talking. And we get, it almost happened. It got to the point where twenty people around a giant boardroom, downtown Manhattan. They’re all shaking their heads yes. This is a done deal in the business world. That’s half attorneys. There are four parties. Ed and me and our attorney. Lucas Film and their attorney. Phillips. General Motors and their attorneys. That group of people saying yes. It’s a done deal. All you have to do is have the attorneys write up the papers, sign the documents and it’s done. Not this time.

Uptown in Manhattan on that very same day, Ross Perot was telling the board of directors they were a bunch of fools for having bought used tools for $5 billion. And that means both the next morning the Wall Street Journal and instantly overnight, anything that had to do with General Motors and Ross Perot was dead. That’s our deal.

So we were frantic. We were running out of time and we had not been able to raise money from anybody. I’d say there’s fifty, forty or fifty different ways of trying pile the money together but not worked. I should mention that somewhere in that process, Steve Jobs had, knew about us, had been kicked out of Apple already, had suggested that he buy us. He had Ed and I come down to his side mansion below San Francisco and he proposed to us that day he’d buy our division and run it. We said, “Nay. I want to run it ourselves but we’ll take your money.” And he ran a number by us and he ran a number by Lucas Film but it was really low and Lucas Film just kissed him off. Because they had this General Motors at about three times the money, two or three, at least twice and maybe three times the money, looking like it was a go on the table.

So, Steve was in there somewhere already and we knew that. We had a relationship with him already. So, Ed and I in our desperation and Lucas Film’s desperation, gave him a call and said, “Why don’t you make that same offer again?”

We think they’ll go for it this time. And he did. And they did. And that’s how we got Pixar funded. Steve put in, paid $5 million to Lucas. Well, the way it actually worked. He gave us two checks. Each for $5 million. That’s big in the name company called Pixar. We turned the first $5 million around and handed it over to Lucas Film to buy technology right, exclusive technology rights. For all the technology we had developed there. Exclusive except Lucas Film also got to use it. And than they other $5 million check was to fund the start up corporation. So, Steve was our venture capitalist. And in return for his $5 million, $10 million really, he got 70% of the company and we employees got 30%.

Andrew: Not for long.

Alvy: Not for long. But I do object when I hear people say Steve bought the company from Lucas Film. No he didn’t. He did a standard spin out. He financed the standard corporations that spin off from another corporation.

Andrew: Like an LBO, or a management buy out within an investor with 70% plus.

Alvy: Just a venture capitalist stepped in with the money. [??] dealt with debt.

Andrew: Right. Right.

Alvy: This is not debt. This is equity. This was equity capital.

Andrew: But in your mind, he was not. You definitely didn’t want him to run the company. You said no and that’s what he wanted. In your mind, he was just the money. The venture capitalist.

Alvy: By this time, he was running his own company called [??], the next company after Apple. An hour and a half away, we were in Marin County above San Francisco and he was in, an hour and a half away below San Francisco. And, our management style, Ed and me, our management style was to keep him out of the building. We would always pull a board meeting. So, he and Ed and I were the board of directors. And, we quickly learned that if he ever entered our building, it would take about a week or two to get it all back into reality.

Andrew: What do you mean? Tell me. How did you personally feel about him back then?

Alvy: Well, he was a magic character. I don’t think everybody knows that. When he starts talking, he’s irresistible. He just weaves this web of magic words and before long everybody’s going “Ahh.”

Andrew: Like what? What did he make people feel?

Alvy: Well, he would paint a story which was usually bologna which is why I had trouble with him. But, people would just believe whatever it was that was spewing out his mouth.

Andrew: For example?

Alvy:

Well, what he would do, here’s an example from our place. He’d confuse things and we were building a piece of hardware. The Pixar industries computer. Steve would come in and make the employees come together and he would give a little talk. And, he would them believing that they could turn out a bullet a month if they [??] could will. In a week that he knew good and well would take a month. But he had them convinced.

By the way, I would watch my employees look at Steve and they would have this look of love in their eyes. I mean he was just so charismatic. He would just grab them. But I also noticed that he was just pouring junk into their minds. So what we’d have to do when he’d leave was, go around and say, there’s no way to turn this out during a week. Can you turn it around? No. Well, get back to reality. What’s it going to take?

Andrew: What would happen if they tried to get it out in a week? Because Steve Jobs. It just wasn’t going to happen.

Alvy: It wouldn’t happen. These things just take their time. You can’t rush them. In fact, we rushed, you’re going to screw them up probably.

Andrew: So, if was the reality distortion field.

Alvy: That’s a great word. That’s exactly what it was. It was complete reality distortion.

Andrew: Of the two of you, were you.

Alvy: Better but once he told them they could do it faster, they would just say the couldn’t.

Andrew: And then would you supposed to be the reality restoration field?

Alvy: Both of us. That’s what we would do. We would say no. No. No. That’s not how it works.

Andrew: Don’t be upset at your people because they couldn’t get it done. You’re supposed to tell people internally don’t be upset at the team because they can’t get it done in a week. This will take a month. It might even take longer. That’s just the way that it is.

Alvy: We’re the expert. Engineer. Hardware engineer. You tell us what it takes. And they would say and they could maybe squeeze an extra day out or something under pressure but not three weeks. That’s just unreal.

Andrew: I’ve heard entrepreneurs here talk about the tantrums that they’ve seen him. The crying sessions one entrepreneur talked about. Did you see any of that with him?

Alvy: No. You have to remember he was not there. He was at [??]. He maybe showed up what once a year for the first several years. I mean our technique was not to think of any excuse we can to not have him in the building. For example, to always hold the board meetings at [??] not at Pixar. And, he would try to get us to move the company. Why don’t you move the company down to San Francisco. Closer to him. Where we all felt some reason absolutely impossible. John Lassiter was living in [??] too big a load. No way we were going to move the company closer to him. He was just too disruptive.

Andrew: And you kept putting him on. His money kept funding the business even when it was losing money, he kept at it. But at one point and we kind of mentioned this earlier there was a breaking point where he said that “hey you know what. I’m putting in all this money. Why do the employees have a big share of this company?” And he did what?

Alvy: Well, it was much more gradual than that.

Andrew: It was? OK.

Alvy: As a company, frankly, we should have failed three, four, five times. We got to the point that we couldn’t pay the bills. That’s failure. But we had one thing on our side that start ups, the usual start up doesn’t have. Steve was too embarrassed after having [??] out at Apple to be seen as a failure on his first investment.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: So, in order to avoid the embarrassment, he would write the check. He would tear [??] apart and he would take equity away from the employees. All makes sense except for the fact that he was, we should have failed. We couldn’t pay the bills. On [??], it wasn’t because he had this great vision for the future. He was just holding on. It was an embarrassment.

Andrew: I see and then.

Alvy: It happened again and again and again. He kept writing the checks until he was in up to $50 million and had taken all the equity away. So, what were, so in a way he bought the company from the employees if you want to have a [??] from somebody.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: It was slow process and many different contracts over several different years. At $50 million, I think that was half of what he had made at Apple. So, he was a big chunk of his fortune was in and not looking good. Right? The hardware business was really not working. He was a great machine. It was super computer for processing but only Disney was buying them. And a few three, four, five letter agencies from Washington that wouldn’t tell us what they were doing with them.

But it just wasn’t working, as a company. What happened was? With Nemo, we kept the animation team there. Of course, that was the whole idea. And they started putting out commercials. You know we tried all sorts of projects, making software, making commercials and stuff to keep it alive, but it just wasn’t working.

Well, [??] was just cranking along in the background all this time. The next five year passed and maybe it was three years, next time passed and Disney knocked on our door again and said, “OK. Let’s make the movie.” And so we started making Toy Story.

Andrew: And they said, “You make the movie for us. You write it but we have the ability to.”

Alvy: We’ll market and distribute it. We make it. So we produced it. We designed it and produced it. And they would market it and distribute it.

Andrew: So, why did you leave?

Alvy: Well, it was. I want to finish with.

Andrew: Oh go for it.

Alvy: It’s important again I’m just trying to get the facts back into position here. Right? Did I say that Steve Jobs had the idea for Toy Story? No, he didn’t. Disney came to us and said, “Let’s make a movie.” And John designed it. Ed negotiated it. OK. And, in fact, I was about to leave during this period. But I stayed there long enough to be sure that the Toy Story deal happened. And there was a problem. Remember I said that John Katzenberg had been fired by Disney?

He didn’t want to work with them. Ed and I were frantic. Here was the big break. Here is what we have been waiting for all these years, preparing for, waiting all along for. And it’s about to happen. It’s on our head animator, you know, the chief artist didn’t want to work with them. So, a meeting was called by Jeffrey Katzenberg in Burbank who was head of animation at Disney. At that meeting, so Ed and I and John and Bill Reeds who’s a technical equivalent to John, and Steve who wanted to meet this guy, Katzenberg. All went down to this meeting and Jeffrey Katzenberg turns out to be a lot like Steve Jobs. Real charismatic. He uses this magic web of words. He reminds me of [inaudible]. He was very explicit. He said, “I try to hire John Lester away from you and he won’t move. In order to work for him, I’m going to work with you.” John thinks I’m a tyrant and I am. But I want you to know if you have a better idea than I have, I want you to know, John, that you have a better idea than I have. You can convince me. You better be right.” And then the meeting turned loose. So the big boys went out of the room. You know. Jobs and Katzenberg. The idea was that John and the technical lead, Bill Reeds, would time spend time on with directors and animators at Disney asking them what it was like to actually work on a movie with Katzenberg at the top. That’s what happens. For several hours, we just hung out. At the end of the day, I’m walking back toward the car, the rental car, going back to Northern California. John and I are out in front of everybody else. I turn to him and say, “What do you think?” He says, “I can do it.” And that was the moment I say, “OK. This is going to happen.” Right. This is going to happen and I started putting together an exit strategy.

Andrew: And here you are, like Moses, shepherding your people to the Promised Land, you’re finally right there at the border.

Alvy: That’s quite a comparison.

Andrew: They cross but you don’t.

Alvy: [inaudible]

Andrew: You don’t’ have a big staff either.

Alvy: Well, I do. It’s in the next room. So, I’m not going on into the Promised Land because I wanted Steve Jobs out of my life. He and I had a terrible face off. And I saw his true colors and I didn’t want that guy in my life anymore. So I came up with another start up idea. And spun it out. My joke is that I sold my first company to Steve Jobs and my second company to Bill Gates because that’s what happened.

Guess who one of the financiers was for my second company?

Andrew: Oh, auto desk.

Alvy: Steve Jobs.

Andrew: How do you mean?

Alvy: Steve. Pixar. Which was Steve Jobs at that point owned 10% of my second company.

Andrew: I didn’t know that.

Alvy: Steve Jobs came through for financing but it was sort of horror show as a person.

Andrew: So you wanted him out of your life. You didn’t want him managing your world anymore. You started your company but you needed funding so you went to Autodesk, the software giant.

Alvy: AutoDesk was the seed capital and the way it was, the deal was originally formulated, I would pay a $25 royalty on every piece of software to Pixar. That’s unworkable scheme. So when I went to second round financing, it turned into a 10% ownership by Pixar.

Andrew: I see. OK. How much did you sell your company to Microsoft for?

Alvy: It was $6.5 million. But what made it sweet was I was paid in Microsoft stock which has split sixteen times. I mean split by a factor of sixteen over the next several years while I was investing.

Andrew: And it was fantastic years for Microsoft.

Alvy: Yes, it has been.

Andrew: That’s fantastic.

Alvy: It was. I’ve had many strokes of luck in life that was one of the sweetest ones.

Andrew: And then you went on to become their first graphics fellow. So, it seems like it was a perfect life at that point. Maybe. There’s nothing perfect but it seems like a really good life then.

Alvy: Yeah. I would. If it hadn’t been for Steve, I’m sure I would have stayed at Pixar.

Andrew: And so was it bittersweet to see Toy Story up on the screen? Sweet because.

Alvy: [??] It was just sweet all the way. It happened. It really happened. It was fantastic. By the way, let’s go back to Toy Story because this is also part of the Steve Jobs thing.

So, we made Toy Story. We. Pixar. I’m leaving after the first part of it and while it’s being negotiated. So Pixar made Toy Story. Ed’s running the company. It’s taken, as it nears completion, it’s taken, by Disney, to New York where the critics see it and they go bananas. And they inform us that it’s going to be a huge hit. This is the point where Steve Jobs rushed in, pushed Ed aside as CEO and took over leadership of Pixar. So, he was there when cameras rolled. [??] that ran Pixar all the time. Always and I think it’s underappreciated. That fact. It was he who ran the company. He was our leader in the early days on Long Island through Lucas Film through Pixar and still runs Pixar. Now, there was this office of the president bologna that said that Steve could be there too but that was part of Steve’s marketing campaign. But again in fairness to Steve because financially, business-wise he was fantastic. He was a scary negotiator. So when really important deals needed to be made. Let’s Steve in. Wham. Things happened and he had this brilliant move. Which was to take Pixar public on nothing except the probability that this movie was going to be a big success. That was a gutsy move. And he turned his $50 million made $1 billion by that move. Kudos. But anyway, he should get all those concrete [??]. Financial and business kudos but when it comes to vision and naming and look and feel and why he funded the company himself that is all malarkey. That’s just a marketing story that’s been.

Andrew: The sense that Pixar shows his taste, that’s not true. He wasn’t.

Alvy: He liked what we did. Sure. It shows his taste but taste that we show is not his. It’s John Lassiter’s. And Brad Berg’s and the other talent that John has pulled in.

Andrew: And still, you.

Alvy: The story there. Well, the guy’s incredibly important to us. There’s just no way around that. That’s for sure. And I thank him highly for it, for you know, supporting us through thick and thin even though it was torture a lot of the times. But I do get upset when people start making him the inventor of it all and that the movies were his idea. And, the name even came from him. That’s just malarkey. He was a great marketer.

Andrew: He was a great marketer.

Alvy: Great marketer and his self-marketing. His marketing of himself was first rate. He even got the biographer of Einstein to do his biography.

Andrew: What did you think of the book?

Alvy: I was worried about it. Walter [??] called me early on. And I said, “Oh, I’ve been expecting you.” He says, “You have.” And I says, “Well sure if you’re doing your history right you’ve got to call me. Right?” I said, “I think this idea stinks.” Here’s one of the world’s great marketers hiring the writer of Einstein to write his own biography. That stinks. He said, “Oh. That’s not what happened. That’s my idea.” It turns out not to be true. It was Steve’s idea. But, he didn’t let Steve have editorial control over the book. That was right thing. And so, the content is what [??] measured. In particular, he represents me accurately. The face off, the famous fight war face off, is accurately presented. Then he calls me the co-founder of Pixar in the opening pages which is true basically. [??] credit over all the years.

Andrew: He has but I see online no one else seems to have show you. Ahha, Wikipedia left you out. How upset are you with that? Let’s talk a look now. I know that when Steve Jobs died. You weren’t on the homepage. It was like three co-founders started this company together. Steve Jobs. Ed and John and.

Alvy: Only Ed as a co-founder of Pixar. I was the other co-founder. John was there at the beginning. That’s for use. And Steve was the money. And the money is never a co-founder. That would make Andy [??] a founder of Google which he’s not.

Andrew: Here. Let’s go to [??].

Alvy: [inaudible] which he’s not.

Andrew: There. Here’s the photo that I’m looking at. This our story. A picture of.

Alvy: Three. Marketing story. [inaudible]. I just [??]. Data process has it right. Micro [??] has it right. [??] It’s not been fun. To have, you know. Clearly, he didn’t want me in the picture anymore because we didn’t like each other a lot.

Andrew: How was he? Was he personal in his attacks on you?

Alvy: Oh my God, yes. He was a bully of the first order. He was the street yard bully.

Andrew: What kind of personal attacks would he make?

Alvy: Well, the famous one was the one in the Iverson book. About the whiteboard where. I guess I should tell you that he and I always, always back talk to him because he would always. His style. The way Steven started out. Is the kind of stuff you like to hear? I kind of.

Steve Jobs was such an interesting guy. It’s been a tale of stories. He would. The way. He had techniques for [??] grabbing attention at a meeting. His one technique was he would walk into a room, and he would say something so outrageous that everybody’s mouth would drop and in that moment, he would take the agenda and it would become his meeting. So, we quickly learned to ignore the first statement out of his mouth. Just let it go by and let’s start the meeting.

Andrew: I see.

Alvy: OK. Another thing we would do. These are board meetings I’m talking about, usually. So, we learned was when his [??] charisma would grab your colleague, we had signs. He’s got you.

Andrew: He’s in the field. You’re in the field.

Alvy: Yes, you’re in the field. Get back to the agenda. I forgot where we were headed with that.

Andrew: Just the way that he would attack and be personal. And I’ll tell you why. You don’t seem bitter about it is why I say. You give him credit for things that he did. You’re not bitter.

Alvy: I’m trying to be just as straight and honest about it, what happened, but not deny myself the credit I think I deserve. So, I basically trust in history and to get it right. But it does have to be addressed.

Andrew: I does seem like history. From what I can see but maybe I’ve been looking at it more carefully than most. Below. Well, it matters it seems like history is right.

Alvy: I’m not going to say bad things about Steve Jobs. People so much want him to be there hero. This is sort of an amazing thing about humans. I guess. That we want our heroes and he painted himself beautifully in this great hero of the modern world. And maybe it’s all true at Apple. I don’t know. I doubt it because I know what he was like at Pixar. But I knew the guy and I know, I know what I know. So, he wasn’t a hero. But people who don’t want to hear that write nasty things to me.

Andrew: Oh, yeah?

Alvy: It just denies. Hello. It’s the truth. You know?

Andrew: And by the way, as we talk I’m looking at the Steve Jobs book in my, on my Kindle. But I should put that away and coming back to your story. When you retired, what did you end up doing? What was the one thing that you said that you were looking forward to actually got to do at the end of all this?

Alvy: Well, there were several things. One was that I wanted to do, a digital camera had finally arrived. We told Kodak back decades ago. What are you going to do when film goes away? And then were, “Well that’s not going to happen? There will always be a need for film.” We knew better. There’s just more fog again. This is going to happen and finally it happened about 2000, I think the micron D1 came out and I looked at that. It’s finally like professional quality digital camera. So, I spent my first year of retired freedom taking pictures. Going to Africa. It was fantastic. Now everybody does it but I got to be there first for awhile.

Andrew: You know, it’s amazing in technology who are visionaries who are the people who create other, who create the future don’t see parts of the future. You talked earlier about Xerox. Not seeing color. You know what. I understand why they didn’t. They said, “Business are buying our stuff. What business wants to mess around with color? They just want the facts on paper. We can’t get into color.” Right?

Alvy: I have a different view now about Xerox than I had as a young Turk. I’ve sat on the other side of the table now as the young Turks come to me with thousands of great ideas. And you know, running a company you just have to pretty much [??]. You have second core competencies as they say. What was the core competency at Xerox? It was black and white. Paper stuff. What did the stick with? They stuck with the laser printer. They have done a really smart thing. They still exist. They’re still very successful. Xerox park still exists. I went to their 40th birthday party a year or two ago. Amazingly. So.

Andrew: That’s what I was going to ask you. What do we take away from this so we don’t make those mistakes? And you’re saying, “Hey, Andrew. Maybe it’s not really a mistake.” Maybe we should take away from it is that these guys need to sometimes focus on their business. They can’t come up with every idea and jump on that and actually continue to be a thriving company.

Alvy: I can say it but Andrew but I really don’t believe it.

Andrew: You don’t believe it. You still think if something spectacular comes along you have to.

Alvy: It was huge. It was the personal computer of history. Silicon Valley basically sprung from that. It’s amazing.

Andrew: All right. I want to. Before I go, just tell people to go to your website because one of the fun parts of your website is you actually have these documents to see the check that Steve Jobs signed over and then your signature and then Ed’s signature underneath it. To see the original documents for Pixar. To see your interests on there. It’s one of the most fun personal sites that I’ve seen. Usually I see a personal site that’s designed to sell one aspect of an entrepreneur and to promote him that way. But I just see your whole personality in it. There it is, it’s Alvyray.com. And we were so proud of ourselves for finding your email address and finding your contact information, and then I realized you have it up on your site.

Alvy: That’s right.

Andrew No wonder all these kooks are emailing you and telling you you’re wrong about this and that. It’s because your email’s available to anyone.

Alvy: Once more, I don’t have to read them.

Andrew You don’t have to respond to them all. Well, thank you for doing this interview and I hope that if people do email you they find that contact info and just say what I’m saying, which is thanks for doing this interview and for sharing this story. It’s great for entrepreneurs like me to hear the story of how you built this tremendous company that really lived up to this vision that was huge. It wasn’t a small vision. It was a huge one that took decades to put together and look at what you’ve built.

Alvy: Can I say one more thing?

Andrew Yeah, you can say it.

Alvy: The way I can relate Moore’s law is that anything good about computers gets an order of magnitude better every five years. That’s a revolutionary speed. Every five years. Ten x. Since 1965, when Moore’s law was a factor of one, we’re now almost at ten billion x. Ten billion times better than in 1965. That’s the revolution that drives all of this. People can see the reason we call it an order of magnitude rather than a factor of ten is that you can’t see beyond an order of magnitude change. If you can, you can probably make a billion dollars. Not only is it hard to look forward, but it’s hard to look back. I notice when I’m talking to younger people, such as yourself, I can see their eyes glaze over when I tell them “Oh, it’s ten thousand times slower.” So what? My world started at one billion billion x, who cares what it was like before? So, what can you do with one thousand x more? Moore’s law. It’s still alive and well. It’s still going out there. Fifteen years from now everything will be one thousand times better. One thousand times smaller, one thousand times cheaper, one thousand times more horsepower. It’ll be better. If you can see beyond one, two, three orders of magnitude, there’s a billion dollars waiting for you.

Andrew So what can you do….

Alvy: One of the points I wanted to make was, I got one glimpse beyond the order of magnitude, right? Because my colleagues and I were so focused on making that first movie, we were actually able to see out four orders of magnitude. Our great success is because of that. Well, I missed a lot of other things that were over the same horizon. Google, for example. What an easy idea. Since I started…. I’m going to hold up my phone here. Just try to imagine this thing a thousand times better. People today are going to be born into this, but this is going to be old and clumsy.

Andrew What do you think will happen when that cel phone is a thousand times better?

Alvy: I don’t know. I tried to think about it the other day. I was talking to a bunch of entrepreneurs in New Mexico and I said, “Can you imagine when this thing is one thousand times better, faster?” It will all fit in a button, say. The camera and everything will all fit in a button. What about the display? Well, maybe it’s on your clothes. You walk into a room, somebody texts, the button is there, it pops up a virtual display. I don’t know, somehow the display has to be taken care of. I don’t know, it’s hard but you try to come up with exercises to make people start thinking about it. I can imagine you’re going to make a video out of this interview. Today, when you click on a video it still takes time to load, right? Give me a thousand x, it’s instantaneous. Probably a movie, at movie resolution, will be a thousand x. I’m not positive about that. All of the glitter in video games should go away finally. They just aren’t fast enough yet to do correct (inaudible), you know, we solved those problems years ago, but not if you have to to come up with a new frame every thirtieth of a second. But that’ll happen with a thousand x. So I can pick off these things that I know will get better at a thousand x, but there are some big ideas out there that I know I haven’t got a clue about. I have to go and think about it. I haven’t got the tools for it.

Andrew And that’s the challenge for us. Not how to make the next app for the next version of the iPhone, but if we want that truly revolutionary business or that truly revolutionary idea we need to think a thousand times or an order of magnitude forward with that tool. Not with the next version of our OS, but with that power, what can we build? We work towards that, and that’s what you did, and that’s the big take-away for me, anyway, from Pixar.

Alvy: What’s magic about our times is you can still get somewhere by imagining what might be unknown, might be beyond the next order of magnitude (inaudible). Because Moore’s law is still active. Gordon Moore himself said so last year, I think. These chips are going 3D, I think. Every time we think we hit a wall with Moore’s law the engineers break through and we get another ten, twenty ….

Andrew Just on Hacker News today I saw some entrepreneurs saying, “Join our startup. We’re about to apply to a Y Combinator with a 3D idea and we need your help.” So, they’re on there.

Alvy: Yeah. It’ll be fun to watch. Anyhow, I’ve had a lot of fun in my life and a lot of fun with this interview. Thank you very much.

Andrew Thank you for doing this interview. I hope I get to meet you in person and to just say, again, thank you for doing this.

Alvy: You’re welcome.

Andrew Thank you all for being a part of it. Bye.